Dr. Henry Huntt was the physician to Presidents James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, and Andrew Jackson. He was an impassioned proponent of the health benefits of mineral spring water, crediting the Red Sulfur Springs resort with curing his lung disease in July 1837. Fourteen months later, however, he was dead and buried.

The hills of southwestern Virginia are a wonderful place to relax, enjoy the outdoors, go sightseeing, and try the mineral springs. In the late 1700s and most of the 1800s, people flocked to the resorts and spas around Roanoke for exactly these reasons. Today, however, only a handful of these places survive. What happened to the others?

I set off to find out on July 24, driving my always-eager BMW Z4 3.0i roadster. The first order of the day was to travel the 287 miles from Catonsville, MD to Lexington, VA. With the dash registering 32 mpg at 75 mph, it didn’t take long. With clear weather predicted for this area, I had carefully washed and polished my Z4 in the hopes of getting some great BMW photos. Naturally it was raining steadily by the time I approached Lexington!

First stop was an 1803 brick house that was the first and only home owned by Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson. He lived here with his wife Anna from 1858 to 1861, when he resigned from the U.S. Army and joined the Confederate forces as a Colonel. (Their daughter Julia was born in 1862, shortly before Jackson’s death.) His house in Lexington is now a museum.

Other, nearby houses in Lexington were rather more elaborate than the Jacksons’ home. The first is now a law office, and the second serves as the headquarters for the Rockbridge [County] Historical Society.

Lexington is home to two major colleges: Washington and Lee University, and a military institute that shall remain nameless, since it is the arch-rival of my brother’s alma mater, Virginia Tech. Washington and Lee began operations in 1749 as Augusta Academy and was well on the way to going broke by 1795, when George Washington donated the then-extraordinary sum of $20,000 in stock. The grateful trustees changed the name of the school to Washington Academy. Today, that original endowment still reduces the annual tuition of each and every student by $1.87!

Following the Civil War, Robert E. Lee became president of the college and introduced a number of important changes, including the school’s famous honor system. After his death in 1870, the college was renamed Washington and Lee University. This is the Lee Chapel, where Robert E. Lee, his father “Light Horse” Harry Lee, and the other members of his immediate family are buried.

Inside, as well as out, the chapel looks very much the same as when Lee was president. The portrait of George Washington is the earliest known painting of the first U.S. President.

Following Lee’s death, his devoted wife Mary commissioned this statue of the General, resting on a camp cot on the battlefield. It’s a striking work of art, and the detail is extraordinary—for example, the weave of the light blanket is clearly visible in the marble.

The Lee Chapel also houses a museum in its basement that includes, among many other things, the exact contents of Lee’s college office on the day of his death. (No photographs allowed, unfortunately.) As I left the chapel, I found the burial spot of Lee’s beloved horse, Traveller, just outside the walls.

As I continued on old Route 60 westward, I discovered this 1955 Buick Roadmaster. It seems to have been waiting for service for quite some time…

The Maury River Friends (Quaker) Meeting House appeared in my peripheral vision, demanding a quick U-turn—and yet another photo, of course.

I had to park somewhere in order to take the photo above, and this driveway was convenient. Fortunately, no children were harmed in the making of this trip report.

This old structure was hiding behind some trees nearby. Was it a small barn? Or the simplest of houses? I couldn’t tell, although the windows on the front side made me suspect that someone used to live here.

My next goal was to find the ghost of Lucy Selina—which, in fact, I did. And I have photographic evidence to prove it. First, I located what’s left of the town of Longdale Furnace, including the house that had been built by Lucy’s master. It still looks a lot like it did in 1883. This 23-room mansion was the home of Harry Firmstone in the late 1800s and early 1900s and is now the

Firmstone Manor Bed & Breakfast. The historical photos of the manor and surrounding area are courtesy of the B&B’s enchanting

History of Firmstone Manor and the Hamlet of Longdale Furnace. It’s well worth a read. (Don’t miss the part about the founder’s son Edwin hanging himself from a tree and the discovery of his wife, who had been buried alive… Every community seems to have its little secrets.)

I’m not sure what the interior of the Firmstone Manor looks like these days, but it used to look like this, swords, pistols, and all!

But what about poor Lucy Selina, you ask? She started her life of service in 1827, received a major refurbishment in 1874, and was joined by another “working girl” nicknamed Australia in 1881. Huh? Oh, I may have failed to mention that Lucy Selina was the name of the town’s original iron furnace.

(What were

you thinking?)

During the Civil War, about 70 slaves were forced to operate the Lucy Selina furnace and produce huge quantities of iron for use in making cannons, ammunition, and other matériel for the Confederacy. One report indicates that the Confederate ironclad ship, the CSS Virginia (better known as the Merrimack) was made from iron produced by the Lucy Selina furnace. (The Currier & Ives print shows the CSS Virginia sinking the Union ship USS Cumberland.)

After the furnaces were purchased by William Firmstone (Harry’s father), numerous innovations and improvements were introduced, and the town of Longdale Furnace grew to roughly 5,000 inhabitants, most of whom were involved directly or indirectly with Firmstone’s business operations. Longdale Furnace became a classic “company town,” with company-provided housing, churches, doctors, etc. This was the Longdale Iron Company office, a log structure built in the late 1820s and expanded in the 1870s by Firmstone. The foundation ruins in the foreground were probably from the locomotive shop. The company ran its own narrow-gauge railroad for transporting iron ore, lumber, and coal to the furnaces and finished pig and bar iron to the market.

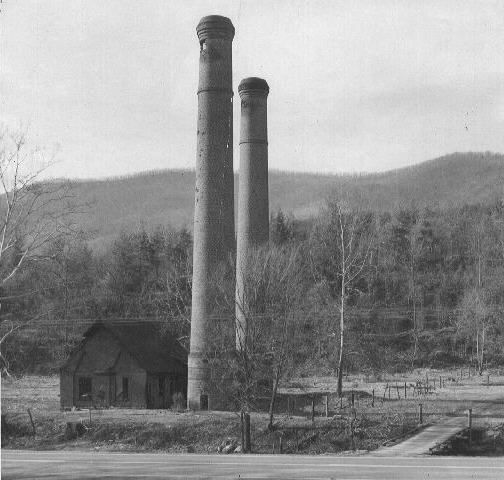

Although Lucy Selina’s original furnace stack was 37 feet tall, after the upgrades there were two 106-foot brick chimneys that were used until the company ceased operations in 1911. Most of the furnace buildings have since been dismantled, but the chimneys still stand today and appear to be in remarkably good shape. (The second chimney is covered by ivy and is only just visible in the upper right of my photo.) The brick machine shop shown in the historical photo still sits behind the chimneys, but it’s heavily overgrown and virtually invisible. The little bridge over Simpson Creek is also still there. But note how the trees and other vegetation have nearly obscured the entire area. You could drive by the chimneys repeatedly without ever spotting them. Long live the ghost(s) of Lucy Selina!

My next quest was to find the Iron Gorge, where the Jackson River carves a deep channel through the Horse and Rough Mountains. My first attempt led me to this Alamo-like building near the river. However, the path I’d identified using Google Maps was summarily blocked off by the CSX Railroad, which apparently preferred to avoid having tall, gawky photographers roaming around on their tracks. My second attempt succeeded, fortunately.

The nearby town of Clifton Forge got its name from an iron forge on the banks of the Jackson River. All that’s left of the operation is this stone furnace. From its top, you can get a good view of Rainbow Rock across the river.

Clifton Forge features three (count ‘em!) three Baptist Churches, just for Cathy and Kim, plus one veritable mansion. Note the substantial expansion of the Clifton Forge Baptist Church, compared to the old postcard.

As I was taking photos, a pleasant young woman stopped and told me that the large house at the end of this block is owned by a 90-year-old woman, who also owns the dilapidated, vine-covered little place behind my Z4. She also told me where to find the mansion, pictured above. You meet a lot of nice people in Virginia.

At 2½ stories, the Clifton Forge railroad station is a lot taller than most. It was built in 1902 and is still used by Amtrak and CSX (the successor to the famous Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad).

The Oakland Grove Presbyterian Church in Selma, VA was built in 1845, replacing an earlier log church. It stopped holding services in 1963 but is maintained in good condition by a nearby Presbyterian congregation. The church served as a Confederate hospital during the Civil War, and a number of soldiers are buried here, including twelve from a Tennessee regiment commanded by Stonewall Jackson.

For anyone seeking a nearly perfect road for motorcycling or driving, Route 220 between Covington and Hot Springs, VA certainly qualifies. It twists and turns up one mountain after another and offers a number of exceptional views as well. The best is of Falling Springs Falls, one of Virginia’s tallest waterfalls. This area had received a substantial amount of rain in the week before my visit, so there was quite a torrent cascading the 80 feet to the rocks below. (For perspective, note the young couple climbing down from the base of the falls.)

A short trail from the overlook leads you to this beautiful pool above the falls. Remarkably, the falls originate with several nearby underground springs in the Warm Springs Mountains, including one in Warm River Cave; there are no other tributaries.

Slightly farther along the trail, you reach the top of the falls. The water looked very peaceful and cool, and it was tempting to wade on in, given the heat of the day. But some things constitute Tempting Fate in such a major way that they just shouldn’t be done!

In an odd footnote to the Falling Springs Falls, I learned that this is not their original location. When Thomas Jefferson visited the falls in the 1770s, they were 200 feet high and much broader. A local fertilizer company, in its infinite wisdom, decided to mine the area around the original falls and diverted the stream to its current location. The first illustration of the original falls is from the

Album of Virginia by Edward Beyer in 1858. The other two are from vintage postcards.

Route 220 also offered this view of Covington in the distance (and the opportunity to exercise the telephoto lens in the ol’ Canon SX40).

I started my tour of Covington in the historic Rosedale section, just across Dunlap Creek from the main city. It’s named after this brick Greek Revival mansion, Rose Dale, which was built by Thompson and Lydia McAllister in 1856-57. I couldn’t help noticing an incredible racket of some sort coming from the area across the creek. It turned out to be the massive Westvaco Paper Mill that dominates Covington—and which was built on land sold to the company by the McAllisters.

An even more imposing mansion sits just down the street. It was built in 1911 by Frank H. Hammond, Sr., who supplied the commissaries for the numerous coal mining companies in the area. It’s a Classical Revival style—and it just happens to be for sale, if you’re interested (and have $795,000 handy). The peek inside is courtesy of Fairfield Farms Realty.

From Rosedale, I set off to drive up Luke Mountain, in search of a view overlooking Covington. I was prompted by the old postcard shown below, but I soon discovered that tall trees and shrubs obscured the view down to the city.

When I reached Luke Mountain Road, I noticed what looked like a tall entrance gate with “Pen-Y-Bryn” chiseled into the granite. I didn’t think much about it as I drove up the long, winding road—but I later learned that William A. Luke, Sr. was the general manager of his family’s West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company (now Westvaco) in Covington, and he chose this mountain to build three magnificent estates for himself and his family, starting in 1917. This photo shows the first of the mansions, named Pen-Y-Bryn. (It, too, was recently for sale, with an asking price of $740,000 in a depressed 2010 housing market. Seems like a pretty good deal for 20 rooms, 6-car garage, pool, and 12,500 square feet…)

You’re probably thinking that I took this photo of Main Street in downtown Covington because of the brilliant red Corvette convertible in the foreground. Well, I admit that it looked really nice, but the subject of this photo is actually the small, nondescript, white building on the other side of the street.

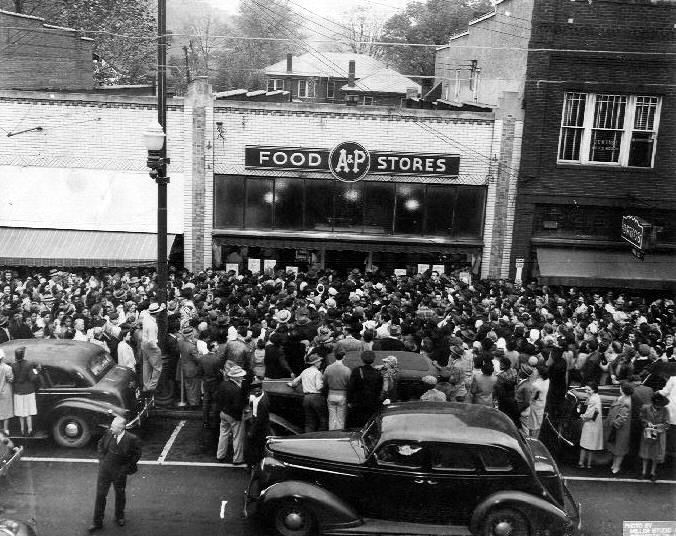

Why bother? Because before the trip, I ran across this intriguing photo from 1946, showing a large crowd trying to buy food at the Covington A&P. It appears to be Spring, World War II has been over for nearly a year, and U.S. food supplies are becoming more abundant. So what was going on? I believe the lines at the store were a consequence of President Truman’s February 6, 1946 implementation of “Emergency Measures To Relieve the World’s Food Shortage.” Following the war, many European and other countries were facing the prospect of mass starvation, and Truman’s edict was designed to divert about 16 percent of U.S. food supplies to other countries. As a result, many American stores would run out of bread, certain meats, and other foods early in the day, leading to long lines of customers anxious to purchase groceries while they were available. (As it happened, the mostly voluntary efforts during 1946-1947 were inadequate to address the problems overseas. The subsequent Marshall Plan of 1948 proved far more successful.)

The Covington City Hall is just up Main Street from what had been the A&P, complete with this monument to soldiers of the Confederacy. It’s been around for quite a while, as shown in the postcard.

Covington seems to have had two railroad stations. This one is referred to as the “depot.” It sat unused and deteriorating for many years but has recently been partially renovated.

Just west of the depot is the “station.” Ironically, neither building is used for train travel; passengers must go to the Amtrak station in Clifton Forge.

My final stop in Covington was at the First Baptist Church, which has been serving its congregation since 1890. The odd black-metal contraption near the front steps appears to be a rather primitive elevator for wheelchair-bound churchgoers.

I made a detour to find Milton Hall, the English Gothic Revival home of William Wentworth Fitzwilliam (Viscount Milton) and his wife Laura Maria Theresa Beauclerk (Lady Milton). They had left England in 1872, when Viscount Milton’s epilepsy worsened, and they bought Callaghan’s Tavern in Virginia to live in with their children and servants. They moved in just before Christmas, 1873—and a week later the tavern burned to the ground as a result of New Year’s fireworks. They subsequently built Milton Hall and lived happily ever after—in this case, for only 3 years and 12 years, respectively, with both Lord and Lady dying at age 37. Milton Hall became a B&B in 1990, but as I approached the mansion I realized that it was now a personal residence. Oops! This is what it would have looked like if I’d been able to get a photo (Flickr image by

gothicartlover).

In Edgemont, I suddenly found myself in what looked like a ghost town from the Old West (admittedly with a slightly art deco look in the middle).

From Covington, I picked up one of the routes from

RoadRunner Magazine’s Roanoke Virginia Shamrock Tour. The more I drove their route, the more I became convinced that Editor-in-Chief Christa Neuhauser and her son Florian had selected the roads based entirely on the number of squiggles per inch that they saw on the map! No kidding, these were among the most consistently curving roads I’d ever come across. I didn’t try to determine the average number of corners per mile, but they certainly contributed to a great many

smiles per mile!

As I drove around this rural part of Virginia, I was struck by how many homes, farms, and businesses were closed and abandoned. Earlier, in downtown Covington, the majority of businesses were either closed or vacant. It all seemed more like West Virginia than the generally prosperous State of Virginia.

By late afternoon, I reached the Roaring Run State Park in Botetourt County and promptly set off to hike up to the Roaring Run Falls. It was a beautiful setting, with the trail crossing and recrossing the creek several times. There were quite a number of lesser waterfalls along the way.

No one was using this natural water slide, although it looked inviting. I could figure out how to start at the top, but I was a lot less sure how to get back to the trail from the bottom!

Finally, I found the main falls and enjoyed the cool breeze and scenery for half an hour before retracing my steps. As I was leaving, a number of teenagers (and their parents) arrived and happily hopped into the natural pool at the base of the falls, along with the family dog.

Another path led me to the ruins of the Roaring Run iron furnace, which operated from about 1832 to 1854.

I don’t usually wonder about the history of bridges as I’m crossing over them, but in this case it turned out to be significant. The Phoenix Bridge was prefabricated in Pennsylvania and started service in the late 1800s near Bessemer, VA for the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad. In 1903, it was moved to its current location over Craig Creek as part of the C&O’s efforts to upgrade their rail lines and bridges. It carried light steam locomotive traffic until being reinforced in 1951 for heavier diesel engines. The Craig Valley Branch of the railroad was abandoned in 1959, and Botetourt County bought the bridge and converted it to automobile traffic in 1961. Who knew?

Railroad Avenue in downtown Eagle Rock has been flooded by the James River so many times that local residents have lost count. The best years of the Farm Supply Store have come and gone, but the 1899 Bank of Botetourt remains open and active to this day, despite having been almost entirely under water during the flood of 1985.

Eagle Rock was well on its way to becoming a ghost town after its lime manufacturing plant shut down operations. Then, the flood of 1985 seriously damaged the only bridge into town from Route 220, cutting off easy access to the outside world. And Virginia’s Highway Department had no plans to replace it. If you look carefully, you can see what little is left of the 1932 bridge in the distance.

You may have noticed that the photo above was probably taken from another bridge over the James River. The town lobbied long and hard and finally convinced the powers that be to build a new, flood-proof bridge into Eagle Rock. It seemed as convenient a spot as any for me to park and take pictures.

Especially since there was a wonderfully scenic wall o’ rock on the western shore of the James.

By now it was after 7:00 PM, with sunset due in about an hour and a half. I had not yet made any arrangements for a place to stay overnight, and there was no cell service in this area. Moreover, the Z4’s fuel warning light had just come on. Accordingly, I drove off to find the lost ghost town of Lignite, VA, reachable only by a steep and badly rutted dirt road, and located in the exact Middle of Nowhere in the mountains of the Jefferson National Forest!

Lignite is considered to be the only true ghost town in Virginia. Although “lignite” is a low-grade form of coal, Lignite was an iron ore mining town in the 1800s. It prospered for many years, with the mines, company houses, stores, churches, and even a theatre. But when the iron ore ran out in 1890, the town quickly began to disappear as well. Getting there was a bit of a challenge, but once again the faithful Z4 conquered even the most primitive of roads.

As the daylight faded, I searched high and low for any of the remaining foundations, chimneys, or other artifacts indicating that a town once stood here. Although I found a couple of small clearings, most of the views looked pretty much like this one.

In the end, I found no signs of this once-significant town whatsoever. But I’ll include

Curtis Warwick’s beautiful photo of the twin chimneys that are still there, somewhere in the trees and bushes of Lignite. (You might enjoy his other photos as well; this fellow is a true photographer.) I’ll be back—in the winter, when the leaves are down—and find for myself what’s left of Lignite.

I drove back down the mountain, managing to dodge the larger rocks on the way, and headed in the general direction of Roanoke. In Oriskany, I spotted the eclectically designed 1903 King Memorial Community Church…

…and a little further on there was a Scenic Mailbox at Slippery Ford Road, plus an awesome, 240-foot-long swinging bridge over Craig Creek. I immediately began walking across the bridge to get a photo—and after less than a fourth of the way, I stopped dead in my tracks. That bridge was jouncing up and down by at least a foot, and it was also tilting violently side to side and threatening to pitch me over the low wire rail and into the creek! I’m not afraid of heights, but I will sheepishly admit that I turned around (very carefully) and gingerly walked back to terra firma. I’ve waded into rapids, climbed rock walls, ventured up and down goat trails by car, motorcycle, and on foot, and done any number of other foolish things in order to get a photo for you all, but I could not cross that dang bridge!

Continuing on, my iPhone eventually reconnected to civilization, and I called Santillane, a nearby stately mansion B&B, in hopes of getting a room for the night. They hadn’t gone to bed yet, but they did politely suggest that I book a room a couple of days in advance, rather than a few minutes…

Thankfully, the Holiday Inn Express in Troutville was happy to see me, and Cuccio’s Italian Restaurant was still open and cooked up an outstanding “turnover”—kind of like a folded-over pizza. And there was even a handy Shell station, since the trip computer had been getting more and more agitated since leaving Lignite. All’s well that ends well, and it had been a great first day of touring.