| BMW Garage | BMW Meets | Register | Today's Posts | Search |

|

|

|

SUPPORT ZPOST BY DOING YOUR TIRERACK SHOPPING FROM THIS BANNER, THANKS! |

|||||||||

Post Reply |

|

|

Thread Tools | Search this Thread |

| 12-06-2017, 05:29 PM | #1 |

|

Lieutenant Colonel

946

Rep 1,910

Posts |

Lost Mansions, Rivers, and Heroes: A BMW Tour of Northern Virginia

Being long overdue for another BMW road trip, I eagerly set off in late September for a tour of Virginia’s mansions, a search for a lost river, and to ponder the nature of yesterday’s heroes. As one of the oldest colonies, Virginia has a wealth of history—much of it in plain sight, but some of it lost in the hills and valleys.

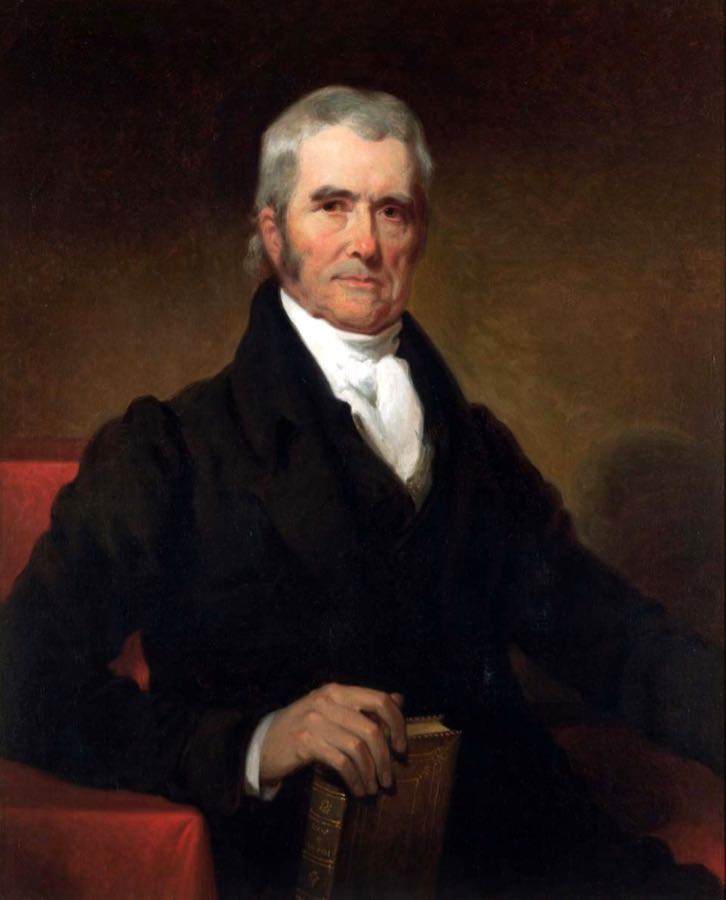

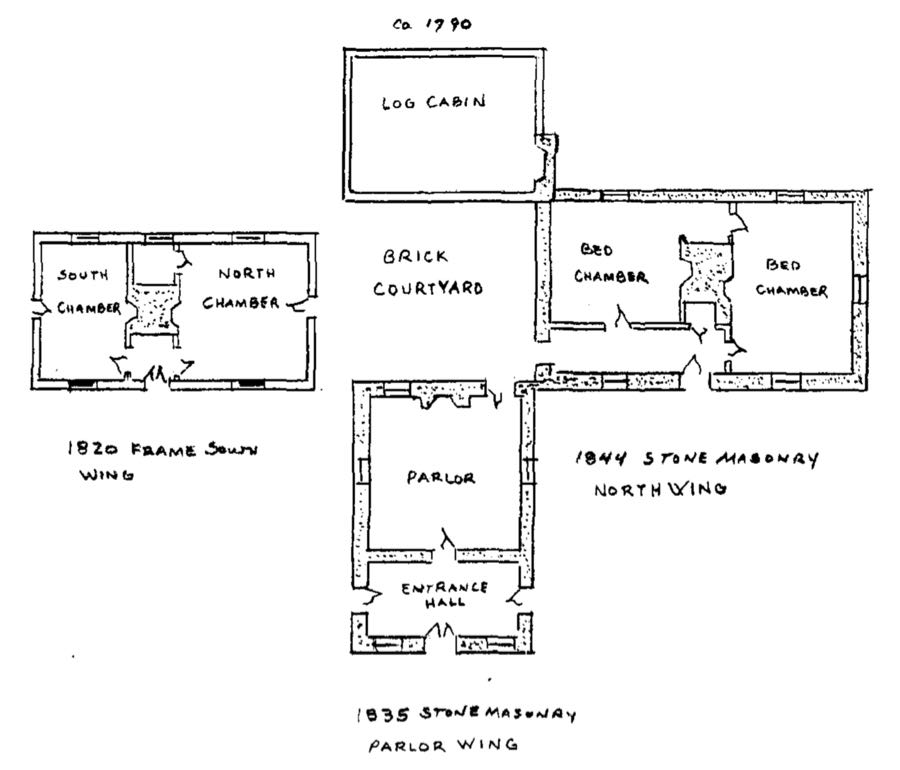

Time Travel My faithful 2013 BMW 335i convertible serves as a veritable Time Machine, able to convey me back to the earliest days of North America. It covered the 90 miles from my home in Maryland to Boyce, Virginia, in practically no time. I hadn’t planned to stop here, but the town was sufficiently quaint to persuade me. To avoid any possibility of door dings, by the way, it’s always best to park next to vehicles without doors.  Boyce was still an uninhabited forest in 1881 when the Shenandoah Valley Railroad laid its tracks through here. I was surprised to discover this prominent train station, given that the town’s population has never been much more than 500. It turned out that the residents raised money and persuaded the SVRR to build a much larger station than it intended, to showcase the prosperity and reputation of the town. The station is still standing, although the modern Norfolk & Southern Railroad hasn’t stopped here in decades.  Millwood is another example of a Virginia town that is virtually unchanged from the 1800s. This is the 1892 Shiloh Baptist Church. For most of its history, members were baptized in the swift-flowing waters of nearby Spout Run.  Behind the church is the village well, which was more convenient than trekking down to the creek.  Anytime you look into the history of the eastern states, you’ll run across the Morgan family. Virtually all of the Morgan men were irascible ne’er-do-wells, given to drinking, brawling, and general mayhem—and quite proud of it. One such person was General Daniel Morgan (1736-1802). He left home at age 17 following a fight with his father, survived 499 whiplashes at the hands of the British Army after hitting his commanding officer, and went on to become an exceptional officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. He was instrumental in the Colonial victories at Saratoga and Cowpens—the latter a direct result of his defiance of orders, naturally.  I had located Morgan’s first home, “Soldier’s Rest,” 5 years ago (see Before There Were Interstates, but this time I was looking for the gristmill he built in 1785 with Colonel Nathaniel Burwell. Millwood is named for this mill, and it is one of the oldest and most complete such mills in the country. It is fully operational, and tours are available through The Burwell-Morgan Mill.   Carter Hall sits just outside of Millwood, having been built in 1792 by Col. Burwell, in significant part from the profits of his very successful mill. It is one of the grandest surviving plantation manors in this area and now serves as a conference center for Project Hope. As indicated by the photo from the Library of Congress, the home is far larger than the central portion seen in my photo.    When Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson made his headquarters at Carter Hall in 1862, he chose to camp with his troops on the grounds, rather than staying in the luxurious mansion. To this day, Stonewall Jackson’s daring and innovative battle strategies are studied at West Point and other military universities, and they have helped U.S. commanders in countless situations for 150 years. Jackson was uneasy with the practice of slavery, and he taught the slaves given to him by his father-in-law how to read (which was against the law). But he fought for Virginia and the Confederacy, including the detestable practice of slavery, and across the country many statues and monuments in his honor are being covered or dismantled. An Accidental Trespasser Continuing on, I found that not all the houses around Millwood are mansions, as suggested by this gradually disintegrating example.  Col. Joseph Tuley, Jr. built his expansive mansion “The Tuleyries” in about 1833. With the forced labor of many slaves, the plantation was an economic success, but in their absence following Emancipation and with heavy damage from the Civil War, The Tuleyries was a ruin. Col. Upton L. Boyce bought the property from Tuley’s widow and later sold it to Graham F. Blandy, who had the estate restored. Today the former plantation is owned by the University of Virginia and operated as an experimental farm.  I had seen The Tuleyries from a distance on a motorcycle outing some years ago, but I was hoping for a closer look. With its latitude and longitude entered into the GPS, I soon found myself on a narrow dirt road in the middle of nowhere. Just as I was beginning to think that the Evil Twins, Garmin and Google, had beaten me again, buildings began to appear, including what looked like a carriage house.  Yep, I’d inadvertently strayed right onto the estate itself. I reasoned, however, that no one would mind a historical tourist, since it was all part of the UVA farm. The Federal-style mansion was imposing and wonderful, having been well cared for since Blandy’s time.  As I stopped for this photo exiting the main entrance, I noticed a little sign that politely proclaimed “Posted: No Trespassing. Keep out.” As I later discovered, the mansion and its immediate surroundings are still privately owned and are most assuredly not part of the UVA farm. Oops… (In fairness, there weren’t any such signs at the far end of the property, where I had entered. Happily, a gardener waved hello, and no one pointed a shotgun or angry dog in my direction.)  Following this incursion, I carefully drove around the Long Branch Manor property, rather than straight up its driveway (which the Evil Twins had marked as a public road). I soon arrived at Old Bethel Baptist Church, near the Shenandoah River. It was built in 1830 and operated for 100 years before closing its doors and falling into disrepair. Fortunately, in 1941 Beverly B. McKay organized the Bethel Memorial Society, which has repaired and maintained the historic church and holds services here semi-annually.  As luck would have it, one of the Society’s trustees arrived to show Old Bethel to a friend, and he invited me to join them. Bev McKay—the grandson of the Society founder—explained that the church is completely original and pointed out that men entered by the main doors on the left and sat in the pews on the left, while women used the door and pews on the right.  He also related that slaves were allowed to attend the services but had to use the separate, side doors on the left and right of the church, climb the tall narrow steps therein, and sit on plain wooden stands in the balcony. Parishioners were baptized in the Shenandoah River, as shown in the historical photo (courtesy of the Bethel Memorial Society).   Bev and his friend had to get to a meeting in Washington, so he left me in charge of the church, asking only that I close it up when I left. Many thanks to him and his ancestors for helping keep this historic place alive.  On back roads, you often find yourself stuck behind slower traffic, occasionally including conveyances that don’t even have turn signals, stoplights, or license plates (let alone airbags, A/C, or more than one horsepower…) But I was in no hurry; it was a beautiful day for a ride or a drive, and we exchanged friendly waves when I was able to pass.  A Jail with a Bar Did I mention that Bev told me no one would mind if I drove up the driveway to the Long Branch Plantation that I had bypassed? He was right, and I learned that the estate is now a museum. It was built in 1811 by Robert Carter Burwell—the son of Nathaniel Burwell of Carter Hall and the great-great-grandson of the almost legendary Robert “King” Carter. As with most of the other plantations in Virginia, Long Branch was in financial ruin after the Civil War but has since been renovated. (Tour information is available at Long Branch Historic House and Farm.)  Long Branch has beautiful views in all directions, but I liked this one the best.  I neglected to mention that I created this tour by stringing together pieces from the Motorcycle Roads website. If these folks don’t have an interesting set of roads in your area, look again—they’re bound to be there. It was a great pleasure to hustle the 335i from one mansion to the next on the entertaining country roads and highways in this part of Virginia. The stately Fairview Farm house is dominated by these two large chimneys on its south side. The interior of the nearly square house has confusing floor plans on both stories, reflecting an unusual mix of German and English designs when it was constructed in the late 1700s for Englishman Joseph Shackelford. Today it is part of the Shenandoah Valley Golf Club.  The first signs of fall colors were evident as the BMW rushed up Great Mountain toward West Virginia.  Fort Warden was built in about 1749 by William Warden, the first settler in this part of (now) West Virginia. The small stockade fort was attacked during the French and Indian Wars in 1758 and quickly proved inadequate for its intended purpose. The fort was burned, and Warden, his family, and others were killed. The town of Wardensville is named for him, although that seems like scant consolation… There I found this unusual former Presbyterian Church from the 1800s. And no, I don’t have any idea why there is a white wooden door standing all by itself near the tower. Perhaps it leads to another dimension, “a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind…”  St. Peter’s Lutheran Church is more elegant, but lacks a “door to nowhere.” It was built in 1934, replacing an earlier one that collapsed.  You can find the old Wardensville Jail just down the street. It started life as a blacksmith’s shop in 1830 but was converted to a jail early in the 1900s. A local old-timer told me that the windows were often used to pass “adult beverages” in to the prisoners, who sometimes left the jail more intoxicated than when they had arrived! (“Bars at the windows” takes on a new meaning.)   When Is a River Not a River? My father loved whitewater canoeing, and his favorite river was the Cacapon in West Virginia (pronounced “cuh-KAY-pon”). As a boy, I canoed with him many times down the Cacapon, through the various rapids, with stops to climb the extraordinary rock outcropping known as Caudy’s Castle. He once told me that the Cacapon is actually the same river as the Lost River, which disappears underground several miles west of Wardensville. Although I had tried on at least two previous occasions to find where the river goes underground, I hadn’t succeeded. On this trip, it turned out to be much easier than I anticipated, in part because the Lost River becomes lost over quite a distance. Here is a typical example, with a dry riverbed upstream and a small pool of water in the foreground. After a rainfall, this section looks and acts like a normal river, sometimes as much as several feet deep.  So far, my route had been on paved roads, and the mighty BMW was much cleaner than usual. It was a perfect day for top-down motoring.  Henry Funkhouser’s ancestors came to America in about 1700 to escape religious persecution in their native Switzerland. Henry built this log cabin in 1845, living here with his wife Mary and (eventually) their 9 children. With one very brief exception, the house and property have been in the Funkhouser family ever since. The front porch was partially enclosed in 1900 to provide a kitchen, but otherwise the house has just one room on the first floor and a sleeping loft on the second. It’s nestled in a narrow valley, with a small brook running alongside. In other words, pretty much perfect.  The Madness of Mobs Did I mention how scenic this part of Virginia is? Views such as this one are repeated over and over along Highway 259 as it winds through the Lost River Valley.  I was hoping to get some lunch at the historic Lost City General Store, but I discovered that they are not open on Mondays. I settled for a photo of this striking mansion next door.  Some years ago, I spent a couple of hours in my BMW Z4 roadster driving on one narrow dirt road after another searching through the West Virginia mountains for the town of Lost City (see In Search of Lost City (or “Half a Mansion Is Better than None”)). After all that, I found Lost City—and discovered that it was in plain sight, right on Highway 259. This time, I motored on through and turned west to look for the log cabin of Henry Lee III in the Lost River State Park. Better known as “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, on account of his excellent horsemanship, he graduated from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) in 1773 and became a hero of the American Revolution. He served brilliantly throughout the war for independence, rising rapidly from an enlisted soldier to a Major General. Only nine Congressional gold medals were awarded during the Revolution, with one of these presented to Light-Horse Harry.   Afterwards, Lee served as Governor of Virginia and then in the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1801, he moved into the Lee Family’s ancestral home Stratford Hall but soon discovered that the hot, humid, summer months there were exceedingly uncomfortable. As a result, he built this modest “vacation cabin” for his family in the mountains of (now) West Virginia. It has been maintained in its original condition; the apparent siding boards are actually the smoothed sides of the log walls.  Here, Light-Horse Harry, his wife Anne, and their children (including son Robert Edward Lee, who was born in 1807) enjoyed the summer months and the medicinal properties of the nearby sulphur spring. It was not to last, however: as a result of several poor business decisions and an economic downturn, Light-Horse Harry went bankrupt in 1809 and served a year in debtors’ prison. Adding injury to insult, during the Baltimore Riots of 1812, Lee was severely beaten and tortured while helping to defend his fellow Federalist Alexander Hanson from an angry mob. He never fully recovered and died in 1818. Not all the old houses in this area are quite so historic. This abandoned farmhouse, for example, was probably not the birthplace, home, or summer vacation spot for anyone famous.  Getting a better look at the place involved crossing Howards Lick Run and climbing a hill. The farmhouse itself wasn’t that interesting, but I was intrigued by this trio of Chevy pickups sitting immediately next to the edge of the ridge. The first and third are 1952 or 1953 models, as best I can tell, while the middle is from 1954. The latter, incidentally, features a rare “airplane” hood ornament, which was an option.  These buildings were part of the abandoned farm. What will be here in another 100 years?  Johannes Matthias came to America from the Alsace-Lorraine area of France in the late 1700s. He built the right-hand portion of this log home in 1797, but by 1825 the family had grown sufficiently to necessitate the addition on the left. By the standards of the time in rural Virginia, this was a very impressive dwelling, and the Matthias family lived here into the mid-1960s.  I used to go “off road” on my 2005 BMW R1200GS motorcycle all the time. Such diversions are less common with the 335i (but apparently not unheard of).  From Ocean Floor to Razorback Ridge By now, I’d wandered back into Virginia and part of the George Washington National Forest. Despite the challenges facing small farms these days, this one seems to be doing okay.  The same cannot be said for all such farms in Virginia, however. Regardless of their well-tended or ruinous condition, they are all scenic.  Seneca Rocks is the best-known example of a “razorback ridge,” but there are many other such outcroppings nearby. This one is at the confluence of Runions Creek and the North Fork of the Shenandoah River, about 30 miles southeast of Seneca Rocks. It’s a rare example where you can see the formation end-on and observe just how narrow it is.  My eminent geologist nephew Ben Webb describes the geological origins of such ridges as follows: Razorback ridges are made of Tuscarora quartzite created during a collision between North America and Africa, which formed the Appalachian Mountains about 440 million years ago. As the mountains rose, erosion brought lots of sediment westward down the mountains into a shallow sea. Over time, these layers compressed and heated, turning sand into quartzite.It’s almost impossible to imagine the forces that acted on the continents to produce such mountains and ridges. Or, for that matter, to comprehend that this part of Virginia was once about 10 degrees south of the equator… But it’s easy to see and admire the end results. Dang, off road again? It’s a wonder that the car is still so clean.  Near Broadway, VA, Christian Sites built this handsome limestone farmhouse in 1801 on property he inherited from his father, Johann Sites. Their family lived here for 106 years, but eventually the house changed hands, became a nursing home, and was abandoned in the 1960s. Fortunately, it has since been lovingly restored.  Proper ventilation is critical for barns, to help prevent spontaneous combustion of hay. But as my fried Neil Peart likes to say, “it can be overdone…”  Also near Broadway is the Tunker House, from 1797. German Baptists were often known as the “Tunker Brethren,” and Benjamin Yount hosted such services here in his home. The main portion of the house features wooden partitions that can be raised to create one large room.  Back in 2015, I’d visited some of the “fortified houses” in the Massanutten Settlement (see Virginia’s Fort Valley and Fortified Houses, Part I and Part II). Although the early settlers came mostly from Pennsylvania and forged a strong friendship with the Native Americans, later ones were not so well behaved. With the outbreak of the French and Indian Wars, settlers had a choice of retreating back east or fortifying their houses against attack. At that time, I’d read about the massive log home known as Fort Egypt, but I was on the wrong side of the South Fork Shenandoah River to get a look at it. This time, I found the long driveway to Fort Egypt—but numerous signs at the entrance made it clear that visitors were not welcome, and I had to settle for this distant view.   Fort Egypt is believed to have been built sometime prior to 1758 by Jacob Strictler, who was an early leader of the Mennonite Church in this area. It has an unusual square design, but, similar to the fortified houses on the other side of the river, its fieldstone basement has splayed openings with rifle slits in the walls to facilitate firing out while limiting exposure. A separate section with a vaulted stone ceiling served as the “refuge of last resort” and was designed to protect the settlers even if the log home overhead were burned.   Advertising can be a very effective way to drum up business, say for the Endless Caverns in Virginia. But one might be able to pick a better location than this vacant general store on a little-traveled road in Hamburg (population: too small to be listed by the Census Bureau)!  The mountains in Virginia offer some outstanding roads for driving pleasure, with Highway 211 being right up there with the best. The paving is usually excellent, traffic is often minimal, and there are even some terrific views—not that you would slow down enough to enjoy them. As always, the 335i is the perfect vehicle for such purposes, with prodigious cornering power and more than enough horsepower to charge up (or down!) the steepest grades.  The Case of the Hidden Mill Somehow, despite my various travels through Virginia, I’d never been to the small town of Washington. On this day, I found this stately edifice, which was built to serve both as the Washington Baptist Church and, on the second story, a Masonic Lodge—the only such structure in Virginia.  Not to be outdone, the African American community in Washington built the First Baptist Church in 1881 and generously allowed the Oddfellows to use the second floor for their meetings.  This handsome house was built in 1750—as the town jail. As best I can tell, it’s now a regular residence. Underneath the exterior stucco, it’s all logs.  Talk about repurposing… The Inn at Little Washington was once a gas station with a dance hall above it and a variety of wrecked cars surrounding it. Since 1978, however, it has been an elegant inn with an award-winning restaurant. After many hours of top-down motoring in the unusually hot temperatures, I was too disreputable-looking to enter the premises, but I did enjoy a look around their beautiful garden. Definitely a place to return to.   If you’re driving along and happen to see a road named “Old Mill Road,” then you have to investigate, right? Sure enough… Not all that many mills survived the infamous Civil War “Burning Campaign” in 1874, but the Calvert Mill was one of them. The oldest section was built in 1799, and the building has held up surprisingly well, given its frame construction. During the Civil War, Union and Confederate soldiers met here under informal truces to trade items such as food and newspapers. I suspect not one person in a hundred in Rappahannock County realizes that this old mill is lurking in the woods. (“Pickets trading between the lines” drawing by Edwin Forbes, 1839-1895.)   This peaceful glade is near the old mill, but I’ll confess that the day had become so hot that I had to raise the roof and max out the A/C to cool down. Well, it’s a really handsome car with the top in either position!  It’s not uncommon to find graffiti on old buildings, but in this instance the graffiti on the Wesley Chapel is almost as old as the church itself (1844). Moreover, it’s etched into the stone. No common rattle cans for the Civil War soldiers who were hospitalized here. Note the drawing of the chapel itself.   Hmmm, rural roads, late in the day… That’s a recipe for a Forest Rat Apocalypse. These cheeky buggers weren’t even afraid of me—they probably would have stayed here all day if I hadn’t honked at them.  The Fate of Yesterday’s Heros? By 6:00 PM I’d reached Warrenton, VA, with enough light left to photograph this beautiful old 1954 Ford F100 pickup, complete with “flower bed.”  I also found the old Fauquier County Jail nearby, built in 1808. But I missed the fact that a replacement jail, built in 1822 complete with a “hanging yard,” was directly behind the original one. At that time, the old jail was converted to a residence for the jailer and a kitchen building was added to the left. Remarkably, the jail complex was used well into the 1960s before being replaced by a more modern facility.  This monument to Col. John Singleton Mosby sits next to the county courthouse and near the old jail. As head of Mosby’s Rangers, of course, he fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. As such, this monument’s days may be numbered.  I fully understand the concerns raised about statues and monuments honoring Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, John Mosby, and many other Confederate leaders from the Civil War. This war was primarily about slavery, an institution that is despicable and horrific. From today’s vantage point, it’s hard to imagine how anyone fighting in support of slavery could be considered heroic. In the 1800s, viewpoints reflected the widespread existence of slavery throughout recorded history. Attitudes were changing, however, with growing realization of the evils of the institution conflicting with the South’s continuing economic dependency on the practice. The Civil War was a long time in the making and was likely the only means by which slavery could be ended. John Mosby himself was an interesting person. On a previous trip, I “followed in his hoofprints,” learning much about him as a soldier and a man (see In Pursuit of the Grey Ghost). He opposed both slavery and the idea of seceding from the United States, but he did support states’ rights and ultimately sided with Virginia in the Civil War. After the war, he worked in support of Union General Ulysses S. Grant to become President and held several positions in Grant’s Administration. As an older man, he befriended a young George S. Patton and enthralled the future general with tales of his military strategies—many of which Patton adopted for use during World War II, becoming one of the Allies’ most effective military leaders in the process. So how do we judge someone like John S. Mosby? Based solely on his actions on behalf of the Confederacy? On the overall scope of his life, both positive and negative? I don’t know the answer to this question. However, I’m confident that the best answer will not be determined by angry mobs, hell-bent on imposing their wills on each other and unwilling to consider these issues with an open mind, discuss them civilly, and reach logical and just conclusions. Harking back to the example of Light-horse Harry Lee, a reasoned consideration of the issue of the War of 1812 with Great Britain would not have involved a mob beating a hero of the American Revolution nearly to death. Nor should the issue of Confederate statues devolve into violent brawls between opposing factions as recently happened in Charlottesville, VA. While we’re contemplating these questions, let’s return to an otherwise-straightforward BMW road trip! Col. Mosby lived in this house in Warrenton from 1875 to 1877. It served as a museum for a year but was not financially viable, and the town council has voted to sell the property.  Would the Union Army Have Burned Skinkersville? After an excellent dinner at the Black Bear Bistro in Warrenton and an overnight stay at the nearby Holiday Inn Express, I was raring to continue my explorations. There’s little left of the village of Buckland, but back in the late 1700s it was a thriving mill town. This home was originally the Buckland Tavern—a Pony Express and stagecoach stop along the main turnpike running from Alexandria, VA to the territories west of the Blue Ridge Mountains (today’s Lee Highway).  Over time, three different mills operated on this site next to Broad Run in Buckland. The last of these was Calvert’s Mill, built in 1899 and still in excellent shape today. (It’s also on private property, which its very polite owner explained to me—sorry about that!)  The last Confederate Cavalry victory of the Civil War took place near here and later became known as the “Buckland Races” or “Custer’s First Stand.” On October 19, 1863, Col. J.E.B. Stuart laid a trap for the Union Cavalry forces commanded by Generals Judson Kilpatrick and George Armstrong Custer. The Union divisions were quickly routed and retreated haphazardly in all directions, leading to the derisive title of the battle.  Next up was Haymarket. Once again, I found a place to park next to a vehicle that didn’t have any doors (on the side, at least).  Haymarket was founded in 1799 by William Skinker, who wanted to call it “Skinkersville.” The Virginia Assembly approved its charter—but only if the name were changed to Hay Market. The Haymarket Town Hall and School was built in 1882 and continued in use as the town hall until 2001, when an electrical fire caused severe damage. The building was rebuilt and is now the Haymarket Museum.  You would think that a town as old as Haymarket would have a town hall, churches, stately homes, businesses, etc. that were older than 1882. In fact, it used to. Located at a major crossroads, Haymarket saw both Union and Confederate troops passing through, camping nearby, and seizing crops and livestock throughout the first 2 years of the Civil War. In late 1862, Confederate “bushwhackers” fired at Union troops stationed outside of town. Several days later, Union forces led by General Adolph von Steinwehr entered Haymarket and burned the entire city to the ground.   The walls of St. Paul’s Church remained standing, and many of the townspeople sheltered in the ruins in the immediate aftermath of the town’s destruction. Five years later, the church was rebuilt and remodeled, adding the belfry and spire and reconfiguring some of the windows (as can be seen by the different bricks on the front wall). St. Paul’s has remained an active church ever since. The building was originally designed by James Wren (a distant relative of the famous English architect Sir Christopher Wren) and used as a county courthouse from 1801-1808. It was converted to St. Paul’s Church in 1834.  Before leaving Haymarket, I spotted this historical School of Rock building, which may postdate the Civil War period somewhat. (I didn’t see any sign of Jack Black, however.) Apparently there are SoR franchises all around the country—who knew?  It wasn’t easy to find Mount Atlas, which was built in 1795. This deteriorating farmhouse is all that’s left of a large and once-prosperous plantation. Charles B. Carter, a great-grandson of Robert “King” Carter, bought the property in 1801 and moved in with his wife (and cousin) Anne Beale Carter. He is buried near the house. My photo is of the side and back of the house, in part because I couldn’t tell where the front was and in part because I was there with the permission of Neighbor A to go onto Neighbor B’s property. A lengthy look around didn’t seem advisable…   A notable feature of Mt. Atlas was the portrait of an unknown young woman—possibly the Carters’ daughter—which was painted on the wall above the fireplace and carried the title “Maiden in Prayer.” The painting and all of the other interior furnishings were removed by the Prince William County Historical Commission in 2000. The house itself has been vacant since 1974. (Image of painting courtesy of John Toler’s interesting article “Mount Atlas—Still a Tangible Link to Haymarket’s Past” in Haymarket Lifestyle Magazine.)  A Magnificent Mill Further upstream along Broad Run, the majestic Beverley Mill ground fertilizer and later flour at a prodigious rate from 1742 into the 1940s. The smaller building in the foreground was the company store and was later used as the Broad Run Post Office.  Two extra stories were added to the Beverley Mill in 1858, making 7 stories in total—with the result that the mill is probably the tallest building ever constructed in the U.S. of coursed stacked stone. Over time, the mill had its financial ups and downs. Eventually, Walter P. Chrysler bought the facility in 1946, added electric motors to power the grindstones, but lost interest and sold out. The mill has been unused since then, and it was severely damaged by an arsonist’s fire in 1998.    The size of this mill is hard to fathom until you go inside. At 83 feet high, it’s just massive. Thanks to the efforts of the local Turn the Mill Around Campaign, the walls have been stabilized, and plans are in development to rebuild the water wheel and millrace.   Chief Justice John Marshall: The Questions Continue I left the Beverley Mill somewhat reluctantly, as it was a fascinating place. I unleashed at least a couple hundred of the BMW’s 300 horsepower westward along the John Marshall Highway, in search of The Hollow and Oak Hill—homes where future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall had lived.  It took some doing, but I managed to locate The Hollow, a modest 1½ story frame house built in 1764 by John Marshall’s father, Thomas Marshall. John Marshall (1755-1835) was born in a log cabin and moved here with his parents when he was 9 years old. By 1771, there were 13 people living in this 4-room house: Thomas and his wife Mary Randolph Keith, their 10 (so far) children, and a Scottish tutor. Unlike many other such house, The Hollow was never absorbed within a much larger dwelling and remains largely original.   Next up was Oak Hill, where John Marshall lived from age 18 until his marriage in 1783 at age 28. When I emerged from the 335i to take a picture, I had that creepy feeling that someone was watching me. It turned out to be true—but the horse probably felt the same way.  The original portion of Oak Hill (on the right in this photo) was built by John Marshall’s father to accommodate his rapidly growing family. John was the oldest of Thomas and Mary’s 15 children, and the Marshalls raised several of their nieces and nephews as well. The original farmhouse has 4 rooms on the ground floor and 3 rooms in the sleeping loft above. That still sounds pretty crowded…    When Thomas moved to Kentucky, John became the owner of Oak Hill. In 1819, he built the temple-form Federal mansion on the left in the photo as a home for his son, Thomas. Oak Hill remained in the Marshall family until 1864 when its owner, a grandson of John, was killed in the Civil War. Oak Hill has remained a working farm. John Marshall served as Chief Justice for 34 years, longer than any other before or since. During his tenure, he developed the Supreme Court into a true, co-equal, third branch of American government, and his court resolved many of the contentious issues involving Federalism versus States’ rights that bedeviled the nascent United States. Franklin and Marshall University in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia, are both named in his honor, as are four law schools, many towns, several counties, and numerous high schools. He also owned more than 100 African American slaves, however, even though he personally was opposed to slavery. He wrote that, “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful.” But his court also held, repeatedly, that property rights were paramount and could not be abridged by governments—with slaves being considered property. What is to become of the statues and monuments honoring John Marshall? (Marshall statue photo courtesy of DC Memorialist.)  The Path to Manassas, and a Singing Bishop With thoughts of these quandaries racing through my mind, I resumed my trip, only to discover that my usually reliable Garmin Montana 610 GPS had decided, “to go on walkabout” (as the Australians say). With no route guidance available, I stopped in Delaplane, VA to see if I could coax the feckless GPS back to life. In the process, I spotted this old railroad store and warehouse along the Manassas Gap Railroad tracks.  Delaplane looks the same as it did in July 1861, when General Thomas J. Jackson’s Confederate brigade boarded trains that took them to the First Battle of Bull Run (Union title), a.k.a. the Battle of First Manassas (Confederate title). By either name, it was the first major battle of the Civil War, and with the arrival of Jackson’s brigade it turned into a rout of the Union forces. It was also where Gen. Jackson earned the nickname “Stonewall.” (“Victory Rode the Rails” painting by Mort Künstler.)  Sightseers from nearby Washington, DC, including a number of Congressmen, had come in carriages and on horseback, many with picnic lunches, to watch the Union Army put an end to the insurrection—only to hastily flee in terror as the southern Rebels broke through the Yankee lines. It was the first time in history that trains had been used to transport troops to a battle. And the battle demonstrated to both sides that the Civil War would not end quickly or without horrific casualties (5,000 dead and wounded at this battle alone).   Most of the colonial mansions in this area of Virginia remain private residences, and most cannot be seen close up. Sometimes, there’s not even a safe place to pull over and take a long-distance photo. So when you’re desperate, you roll down the window and take the picture as you’re driving by! This is Mount Independence, which started life as a small log cabin in 1758, gradually gained frame and brick additions, and—eventually—was surrounded by a large stone mansion. Some of the logs from the original cabin are still visible in the interior. (Proper photo of Mount Independence courtesy of the exceptional photographer(s) at Beltway Photos on flickr.)   There are still a lot of active farms left in this area. This one is near Paris, VA and Sky Meadows State Park.  Bishop’s Gate Chapel started life as a chapel in 1910-1914 but was soon converted to a school. Sometime between 1938 and 1950, it became a home and has been used as such ever since. It still looks like a chapel, however, with its large, diamond-pane windows and a prominent bell tower. It also has large stone buttresses on each side (barely visible on the left in the photo).  The chapel was named for Bishop Charles C. McCabe (1836-1906), who had lived across the road while serving as the Chancellor of American University. At the start of the Civil War, the Bishop helped raise a regiment of soldiers for the Union Army. He served as their chaplain, was captured by Confederates at Winchester, and sent to the infamous Libby Prison in Richmond. After his release, Bishop McCabe gave a lecture at the Hall of Representatives in the Capitol building (now Statuary Hall), telling the story of the horrific conditions at the prison and how he taught his fellow inmates The Battle Hymn of the Republic to lift their spirits. Bishop McCabe then led the audience in singing the battle hymn. Such was their enthusiasm and emotion while singing, most of the group was on their feet and crying by the song’s conclusion. In the hubbub that followed, President Abraham Lincoln, with tears streaming down his face, called out “Sing it again.”   Bears Den Traveling along Blueridge Mountain Road, one sees the formal stone entrances of numerous estates. The mansions, unfortunately, are set well back from the road and are generally out of sight (and camera range). However, Bears Den is a notable exception. It was built in 1933 as a summer home for Dr. Huron Lawson and his wife, soprano Francesca Kaspari. After their deaths in the 1960s and a failed attempt at developing the mountaintop area, the estate sat vacant for 20 years. Ultimately, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy acquired the property, rerouted the trail from local roads to the mountain top, and established Bears Den as a low-cost hostel for hikers.   The Appalachian Trail is only 150 yards from Bears Den, and this section of the trail is known as the “Roller Coaster.” The Bears Den Overlook is a huge rock outcropping offering an excellent view of the valley 600 feet below and the Harry Byrd Highway in the distance. Here is Yr Fthfl Srvnt doing a little exploring. (Historical postcard of Bears Den Overlook courtesy of Welcome to Bluemont.)     The Last Lynching I had to head back home after Bears Den, having promised to photograph a high school volleyball game, and I later realized that I’d missed a whole section of my trip when The Evil GPS malfunctioned. Accordingly, I snuck back to northern Virginia a few days later to find the last few places I’d wanted to see. On the way, I happened across The Rectory, from 1900. It was built as part of a huge apple farm by the aptly named Gilbank Twigg, Esquire.   The Beulah Baptist Church looks down over the small town of Markham, VA. It was built in 1903, replacing the original log church from 1870. Judging by its immense parking lot, the church is thriving.  Gilbank Twigg, Esq. wasn’t the only one growing apples in this part of Virginia. Hartland Orchards is still going strong and still using this 1875 warehouse as part of their business. It’s a “bank warehouse,” built into the side of a hill in the same way as bank barns.  In 1819, a Free Church—available for use by all denominations—was built in Markham on land donated by Nimrod Farrow, Jr. As the various religions built their own houses of worship, it became the Goose Creek Primitive Baptist Church and in the 1980s began to share alternate Sundays with the Markham United Methodist Church. During the Civil War, the Confederates used this church as a hospital while, later, the Union Army used it as a stable for horses.  The many members of the Marshall family built quite a number of stately houses in Fauquier County, VA. Chief Justice John Marshall’s brother, James Markham Marshall, built Fairfield and moved here with his wife Hester in 1814. With my unerring sense of direction, I have once again managed to get a photo from the back of a historic mansion, rather than the front—but it’s impressive either way.  Fairfield stayed in the Marshall family until 1880. It had several owners after that, including the Baroness Johanna von Reininghaus Lambert of Belgium, who bought Fairfield in 1939. She had emigrated to avoid the conditions in war-torn Europe and happily settled into one of the farm’s log tenant houses. She went back home after World War II, and J. Willard Marriott bought the farm a few years later. Bill, as he was known, renovated the mansion, which had fallen into disrepair. Marriott had opened a 9-stool root beer stand in Washington, DC in 1927, expanded it into the Hot Shoppe Restaurant, and then created a chain of Hot Shoppes across the country. Eventually he founded the Marriott Corporation, adding Big Boy and Roy Rodgers restaurants along the way and building his first hotel in 1957. The rest is history, as they say. Today, James Marshall’s farm is owned and operated as the Marriott Ranch, and the historic mansion is the Inn at Fairfield Farm.  As fate would have it, in 1932 a farm worker was shocked to discover a badly decomposed body hanging from a tree branch at Fairfield Farm, near the foothills of Rattlesnake Mountain. The body was identified as one Shedrick Thompson, an African American tenant farmer who had lived nearby. He had been the subject of an intensive manhunt for the past 2 months, after he had viciously attacked his employer, Henry Baxley, and abducted, beaten, and raped Baxley’s wife Mamie. When the body was found, an angry mob soon assembled and burned it to ashes. The local coroner ruled that Thompson had hanged himself, committing suicide rather than facing justice for his crimes.  As recounted in the engrossing book The Last Lynching in Northern Virginia: Seeking Truth at Rattlesnake Mountain by Jim Hall, the official ruling was unsupported. Most local residents believed that Thompson was lynched, and some even bragged openly about their role. However, political forces were at play: Following two lynchings in 1926-1927, Governor Harry F. Byrd signed into law an anti-lynching act, making Virginia the first state to specifically define lynching as a state crime. In 1932, as a candidate for President of the U.S., Byrd was pointing proudly to this legislation—and the last thing he wanted was for a new lynching to be acknowledged.  The available evidence, however, indicated that Shedrick Thompson had been captured and hanged just a few days after he attacked the Baxleys, the work of one of the unofficial posses—also known as an angry mob. Although specific perpetrators were suspected, no one was ever arrested or brought to trial for Thompson’s murder. He was the last person to be lynched in Virginia. A House per Child? The Leeds Episcopal Church has seen its share of history during its 175 years in Fauquier County. The parish dates back even further to 1769, with the first minister being James Thompson—the tutor who lived in The Hollow with the Marshall family. During a nearby Civil War skirmish in 1862 between Confederate Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry and Union Gen. Alfred Pleasonton’s troops, a cannonball pierced one of the church’s walls. The fused shell exploded inside “doing some damage to the melodeon and the pews,” according to historical accounts.  The interior of the Leeds Church was destroyed by a fire in 1873, but the walls were undamaged. As the area’s economy began to recover from the war, funds were available to rebuild the sanctuary, and the church has been well maintained ever since.  The church and all the graves in its cemetery face east—all set for the Second Coming, as was the practice then. A great many Marshalls are buried here, along with Amblers, Striblings, Yates, and others. Henry and Mamie Baxley are here, too, having passed away in 1983 and 1997, respectively. After the assault, Mamie never again stepped foot in their family home Edenhurst.  There weren’t any formal schools in this part of Virginia in the 1800s, so landowners often hired tutors for their children or built small private schools for neighborhood children. One such school was “The Abbey,” established by John Marshall’s nephew, Major Thomas Marshall Ambler and named for its teacher, Ezra Abbott. I thought I might have trouble identifying the schoolhouse, but this unusual planter made it easy.  The Abbey has log, stone, and frame sections. The stone part is believed to be the original section of the school, with the log portion serving as a dwelling for the teacher. I believe the old school is still owned by Marshall descendants and is now used as a dwelling.  Maj. Ambler and his wife Lucy acquired property in Fauquier County in the early 1800s and moved into an existing small log cabin. Legend has it that each time a baby was born into the family, the Amblers added a new building, adjoining the original cabin. In reality, they had 9 children but “Morven,” as they named their home, had only four wings. They were arranged in a rectangular pattern, with an open courtyard in the middle.  Maj. Ambler trained as a lawyer, but dairy farming was his primary occupation. The cows at Morven produced 40,000 pounds of cheese annually before the Civil War wreaked havoc on the farm. As Lucy Ambler wrote in her diary on March 23, 1863, “[The Union soldiers] have become so purposely desperate that they are willing to bend their necks to the yoke of despotism. They talk as strongly as ever of starving out the South … I cannot help repeating, behold what desolation this war bringeth upon us. Our church is broken up, our children gone away. Our enemies have endeavored to deprive us of everything … We are but pilgrims.” (Painting of Morven courtesy of Melanie Chambers Hartman.)  As I gazed at Morven from a distance, it was hard to tell which part of the house was which. It turns out that the log cabin was replaced with a new addition, which together with the frame and stone sections were enclosed into one large mansion in 1954. The property stayed in the Ambler/Marshall family through the early 1900s, when it was sold to Leroy Baxley—the father of Henry Baxley. Interestingly, Morven was acquired in the late 1940s by James R. Green and his wife Caroline Marshall Ribble, both of whom were great-great-grandchildren of John Marshall. Caroline continued to live there until her death in 1995.  With my mind crowded with thoughts of Virginia’s multi-storied history, from romantic mansions, to horrific slavery, to the Civil War, to mobs and lynchings, it was time to have the 335i Time Machine transport me back to the present and my hometown of Catonsville, Maryland. It was a fascinating tour, full of the expected historic and scenic sites but also remindful of the current controversies facing the U.S. The only hard and fast conclusion I reached was that nothing settled by an angry mob will be settled sensibly.  Rick F. PS: Unless otherwise noted, historic photos are courtesy of the Library of Congress, Wikipedia, or the National Register of Historic Places. |

| 12-07-2017, 01:15 PM | #2 |

|

New Member

0

Rep 5

Posts |

Rick,

It is always a pleasant surprise to discover one of your interesting travelogues online. Thank you for sharing your excellent adventures with fellow Bimmer enthusiasts. |

|

Appreciate

0

|

| 12-07-2017, 05:25 PM | #3 | |

|

Lieutenant Colonel

946

Rep 1,910

Posts |

Quote:

You're very welcome, and I'm glad you enjoyed the report. I just love hustling around the countryside in the 335i and finding old, interesting places. The more forgotten they are, the better! Even the BMW seems to enjoy it, particularly climbing steep mountain roads with the engine turning 5,000 rpm or higher… A terrific "partner in adventure." Rick |

|

|

Appreciate

0

|

| 12-10-2017, 07:11 PM | #5 |

|

Brigadier General

3854

Rep 3,004

Posts |

Rick - your tasteful pics and narrative are simply incredible - we love your insight and perspective and are grateful for your care.

__________________

Racerbruce

|

|

Appreciate

0

|

| 12-11-2017, 08:22 PM | #6 |

|

Lieutenant Colonel

946

Rep 1,910

Posts |

|

|

Appreciate

0

|

| 12-11-2017, 08:24 PM | #7 | |

|

Lieutenant Colonel

946

Rep 1,910

Posts |

Quote:

Great, I'm glad to hear it! The trips are terrific fun to take, and the reports are nearly as much fun to write up. Sounds like a win-win for sure! Rick |

|

|

Appreciate

0

|

Post Reply |

| Bookmarks |

|

|